(This “SoBo Made” feature story first appeared in the October 2023 print edition of the South Baltimore Peninsula Post.)

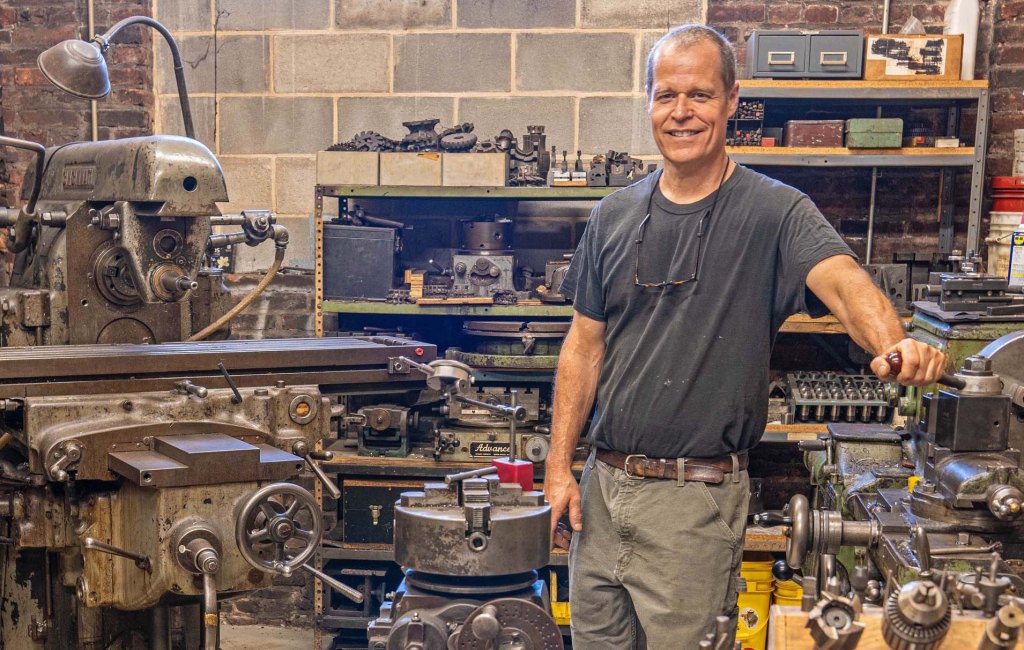

Jonathan Maxwell, a SoBo maker on Light Street for nearly a quarter of a century, does not fit easily into any one creative category.

He is a multimedia artist with a recently installed triptych in an upscale Baltimore hotel offering a bird’s-eye view of Baltimore’s harbor. He is a furniture maker with custom-made cabinets, tables, and lamps in private homes in France, Canada, and throughout the United States. He is an architectural décor designer who crafted the distinctive look of the Charles Theater lobby (including ticket booth and concession stand). And he is a metal worker who built his own hydraulic press to bring 60 tons of pressure to shaping his designs into solid objects.

He’s been called an artist-craftsman. A designer. A concrete, wood, and/or metal artist. His website dispenses with categories altogether, stating simply that the Jonathan Maxwell Studio (1438 Light Street) produces “visual art and objects.”

The common thread in his creative output is Baltimore’s now faded industrial landscape and the once-dominant medium of that era: metal. Growing up in Parkville on the northeast corner of the city in the 1980s, Maxwell saw the remnants of that landscape. “By the time I was an adult, Baltimore’s industrial landscape was kind of a thing of the past. I was attracted to the mystery of what that was all about and curious about the history of what it was like to be in a city that was actually making things. I got interested in metal and fabricating things as a way to learn about that history on a deeper level, by actually learning the skills.”

Two years after graduating from MICA in 1991, he established his own studio, renting space in the Broom Factory near the Canton waterfront. “I started making little pieces of furniture, cabinet-based things, out of wood at first. At some point, I discovered metal and that was really cool. It felt very empowering to put pieces of metal together. So I started teaching myself metalworking and learning from as many people as I could.”

Maxwell got his hands on actual pieces of Baltimore’s industrial past when he helped sculptor David Hess assemble his massive “Working Point” sculpture of rusted machine parts on the Baltimore Museum of Industry campus in 1997. “I did a bunch of welding on that, plus drilling holes and bolting things together.”

He was also busy in the late 1990s crafting home furnishings which sold well at furniture shows in Philadelphia and the annual American Craft Council show in Baltimore. And he landed the design project that is probably his best known work in the city to date: the lobby of the Charles Theater.

The movie theater was undergoing a major renovation in 1998, morphing from a single screen to a multiplex by expanding into the former Godfrey’s Famous Ballroom next door. Maxwell, who had worked as a projectionist at The Charles during art school, pitched a design for the theater’s lighting to the developer. The project’s architect liked it so much that he gave Maxwell free reign to design and build the lobby’s décor and various other features.

It was at this same time that Maxwell’s artwork led him to South Baltimore and the purchase of space on Light Street with his wife. “We had decided we were going to start looking for a space to buy. One day we were dropping some artwork off at the School 33 Art Center for their annual benefit. We walked out of the door and saw that the building across the street – the Cummins Public Service Radiator repair shop – was for sale. And that was pretty much it.”

The building came with the adjoining rowhouse, and the couple moved in and stayed for 12 years. “I didn’t know a whole lot about South Baltimore at the time,” he recalls. “Our son was born here. It was good. I learned all about tight parking.” They now live in Baltimore’s Charles Village/Old Goucher neighborhood, but the Jonathan Maxwell Studio continues inside the ground floor of the unassuming two-story brick building on the corner of Birckhead Street.

Here Maxwell creates his “visual art and objects” in a series of connected spaces, each devoted to a different aspect of his creative interests. A machine shop is packed with hulking metalworking machinery, including a drill press, band saw, horizontal milling machine, and lathe. Another area is devoted to metal-shaping machinery and welding, with an English Wheel, Pullmax machine, a large Acorn welding table, and his homemade 60-ton hydraulic press. There’s also a woodworking shop and a small painting studio just behind the display room that faces Light Street.

With this diverse array of tools at his disposal, Maxwell tackles a shifting mix of projects that flex his personal creative muscles and/or his problem-solving skills while engineering objects from his own designs and those of others.

During the Peninsula Post’s visit to his studio in September, we saw several projects at various stages of completion. Two antique, elaborately carved pieces of wood, about a yard high and several inches across, stood on a workbench. These, Maxwell explained, were sent from a client to become part of a table that he will design.

His furniture projects are now typically commissioned and often by clients that he has worked with for years. “I think what they like about what I do is not only my aesthetic sensibility but my engineering sensibility. They’ll say ‘Hey, Jonathan, I’ve got this crazy idea’ and we’ll talk about the project and I’ll elicit from them their ideas. I do some 3D drawings on the computer and come up with a design and model it.”

Standing against a wall of the studio was a finished project waiting for installation in a new Highlandtown restaurant: a set of 16 bright-red, wedge-shaped metal frames, each about eight feet tall. When assembled, the metal frames will become a ceiling canopy piece some 20 feet across. This project, Maxwell explains, evolved from a design-and-build job to one that mainly used his metalworking skills.

Nearby, mounted to a white wall, is Maxwell’s latest artwork-in-progress, a mixed-media wall sculpture that, he describes as a contemplation on the death of his father. The piece, titled “Mourning,” combines a shadowy pinhole photograph of waterside buildings with metal cubes attached, all enclosed in a frame of metal parts.

Making visual art is something he likes to reserve mainly for personal projects like this one, he says, rather than something to make a living from. “I go through little phases of making visual art and then I won’t do it for a year or so. I had a show just before the pandemic and I sold a few pieces out of that, but I don’t want that work to be something I’m depending on.”

He did, however, recently complete a commissioned artwork that you can see at Cindy Lou’s Fish House inside the Canopy Hotel in the Harbor Point development. Three free-rolling panels hanging from a metal frame mounted to the wall depict a bird’s-eye view of the harbor from a point above the hotel. While the waterfront across the harbor on the SoBo peninsula is rendered from a modern-day photographic view, Harbor Point itself is filled with a sketch of the site’s industrial past: the sprawling Allied Chemical chromium plant that once stood there.

Maxwell’s work has also kept him busy outside his studio in the last few years as he continues his collaboration with David Hess. He’s helped the sculptor with fabrication and installation of his “Waterwheel” sculpture in Ellicott City and “Relativity” at the Greensboro (N.C.) Science Center and is currently working on a new Hess project at Frostburg (Md.) State University.

To get a glimpse of what’s next on Maxwell’s creative agenda, keep an eye on the display windows of his Light Street studio. “I’m going to redo this area,” he says, noting that it has been sparsely populated for years. “I’ll probably focus on the visual artwork, but I do want to have some furniture stuff in there, too. It’s weird. I don’t do any market research. I just get a little sense of what I want to make. And right now, I really want to make some lamps.” – Steve Cole