Three hundred years ago, the actions of one English settler prevented SoBo from becoming the heart of Baltimore City.

(This article originally appeared in the February-March 2024 issue of the South Baltimore Peninsula Post.)

The landscape of downtown Baltimore and the adjacent South Baltimore peninsula neighborhoods we’re familiar with today could have turned out dramatically different if one man – John Moale from Devonshire, England – had not settled here in the 1720s, before Baltimore was even a dot on a map. City Hall might be standing in modern-day Latrobe Park. High-rise offices and banks might line E. Fort Avenue. And blocks of rowhouses might climb northward along Charles Street from the Inner Harbor.

Moale held the rights to hundreds of acres of what is now our SoBo peninsula before anyone proposed creating a “Baltimore Town” along the Patapsco River. He eventually controlled most of the peninsula and influenced where Baltimore was built and how the early town grew after his death.

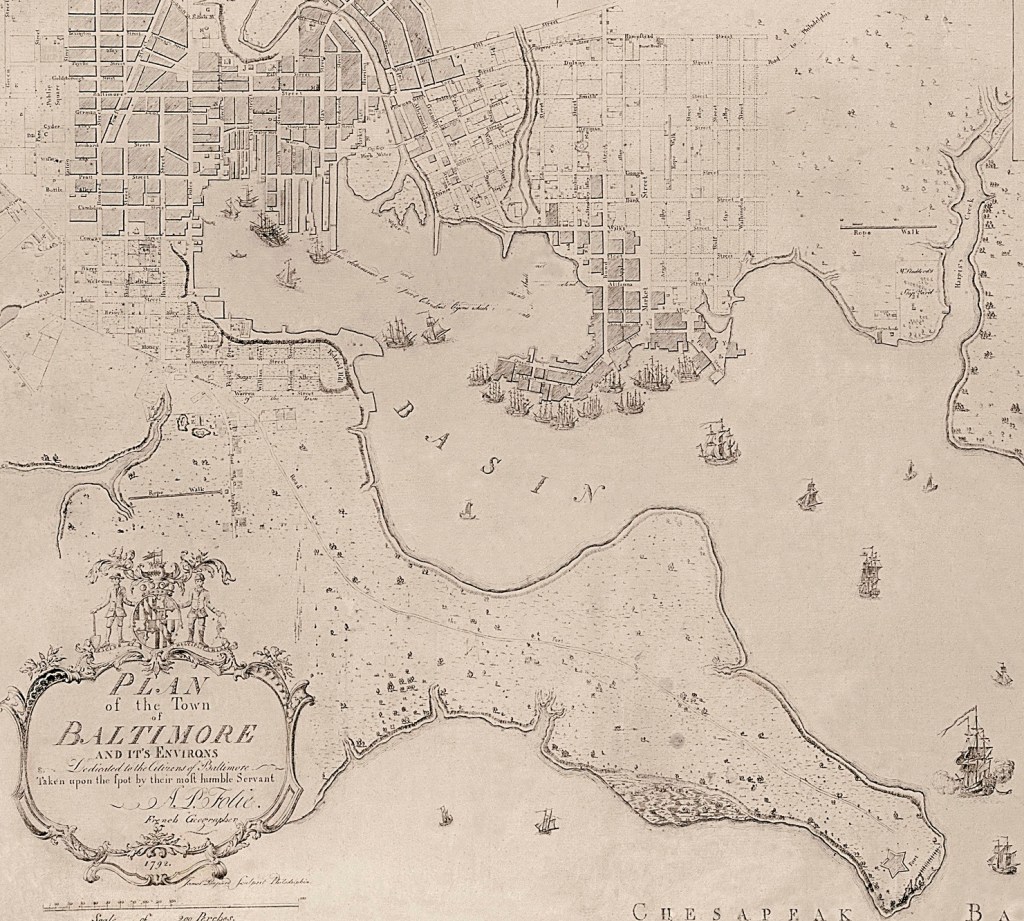

A view of Baltimore from as early as 1815 clearly shows Moale’s influence. The tightly packed streets of the city along the north side of the harbor fan out in all directions, except for the south. The entire peninsula, from Federal Hill to Fort McHenry, is covered with meadows and trees, with few buildings or streets. The contrasting patterns of urban development on both sides of the harbor today can be traced back to Moale.

The story of European settlement of the Baltimore area does not really start until the early 1700s, long after English explorers and settlers first arrived in Jamestown (1607). Once the King of England granted the Calvert family a charter to establish a new Maryland colony (1632), towns began to sprout up along the lower Chesapeake Bay: St. Mary’s City in 1634, Providence (later Annapolis) in 1649. When Baltimore County was created in 1659, encompassing much of present-day north-central Maryland, only about 2,000 settlers lived in the huge tract, but none on our peninsula.

The first landholders on the peninsula received “patents” from Lord Baltimore, the proprietor of the Maryland colony, in the 1660s and 1670s that gave them exclusive use of an area in exchange for minimal annual rents. The three largest initial patents were “Whetstone Point,” the 50 acres where Fort McHenry now stands; “Upton Court,” 500 acres stretching from current-day Latrobe Park west to Riverside Park; and “David’s Fancy,” covering 100 acres in the Spring Garden-South Baltimore area. These three tracts would eventually grow over the next century to encompass most of the peninsula.

Few, if any, settlers arrived here before the early 1700s. The land itself was judged to be poor quality because it was not suitable for growing tobacco, which was the primary cash crop in Maryland at the time. The peninsula remained primarily virgin forests, with a few meadows and marshland. There were so few newcomers to the area that a bill passed by the provincial legislature in 1706 to make Whetstone Point the official port of entry for Baltimore County failed to establish the port at the time due to lack of interest.

What eventually did start to attract settlers to the area was an industry that few would associate with Baltimore today: iron mining. In 1608, during his exploration of the Chesapeake Bay from Jamestown to its source at the Susquehanna River, John Smith had sailed around the peninsula all the way to current-day Federal Hill. He noted the rust-red color of the clay along the shore resembled “bole armoniack,” the term used in England for iron-ore-bearing soil.

Iron exports to England from the Chesapeake Bay region began to be big business in the early 1700s and continued through the American Revolution. The British-owned Principio Company was a big player, establishing ironworks in Maryland around 1715 and mining peninsula iron ore deposits at Whetstone Point. By the 1760s, there were over a dozen iron furnaces and forges in Maryland producing several thousand tons of iron a year.

Enter 25-year-old John Moale, the eldest son of a successful shipmaster who had worked in the iron business in England. He arrived in Maryland around 1720 to make his fortune. Settling in Annapolis, he quickly established influential connections, married into one of the province’s leading families, and soon became a member of the legislature.

In 1724, Moale made his first land acquisition on the peninsula by claiming a patent for 50 acres on the peninsula’s southern shore around the point at modern-day Ferry Bar. In 1727, he took over two adjacent patents, increasing his holdings to 400 acres of what today would be most of Port Covington.

On this land, over the next decade, Moale created a thriving, diversified commercial enterprise – a sort of private mini-town. In addition to his interest in iron, he operated a trading business with three ships, a merchant store, and brick kilns. The main road to Annapolis ran through Moale’s land to Ferry Point, where he operated a ferry service.

Moale had a good thing going and was eager to see it grow. But, in 1729, the provincial legislature considered a plan to create a new town on the Patapsco River to encourage more settlement. No town existed in the area at the time, although a few early settlers, like Moale, lived here and there near the river and its tributaries. Whetstone Point at the eastern tip of the peninsula was selected as the location for the new “Baltimore Town.”

The spot looked ideal on a map. It sat at the entrance to both branches of the Patapsco River, so commerce could grow along two flanks of the peninsula, as it had on Manhattan Island in New York. Moale was having none of it, however. With the aid of fellow peninsula landholder John Giles, who controlled Whetstone Point and neighboring Upton Court, he argued against the location before the legislature, citing the valuable ore deposits there.

As a result, the plan was defeated. Just a few months later, however, it was revived with a new location for the town: 60 acres on the north side of the Northwest Branch at what today would be the Inner Harbor, right in the heart of the central business district (N. Charles and Baltimore streets). The plan was approved, and the town that would become a city was born.

As Baltimore Town was getting slowly on its feet, Moale increased his landholdings on the peninsula. He added 300 acres of Upton Court in 1732 and nearly 300 acres in David’s Fancy in 1737. By the end of the decade, he controlled more than 1,100 acres, most of the peninsula, except for a small tract along the harbor, west of current-day Federal Hill, and the iron beds along Whetstone Point that Principio controlled.

Moale never realized any plans he might have had for our peninsula. He died in 1740 at the age of 44, leaving his estate to his sons John, Jr., and Richard. His influence over the future of the peninsula and the slowly emerging town nearby, however, continued from beyond the grave. His will, using an English legal convention known as “the dead hand,” prohibited his sons from transferring his landholdings to anyone but their own heirs.

So as Baltimore Town gradually expanded with newcomers buying lots from established landowners, much of the real estate to the south was not available. The onset of the American Revolution proved a boon to the town, with its shipbuilding, trade, and manufacturing along the Jones Falls in high demand and colonists flooding the town from other East Coast ports occupied by the British. The town expanded in every direction except south.

Our peninsula remained largely a backwater. The Moale brothers continued to operate their iron ore and brick-making businesses, clearing the forests to make coal to fire their furnaces, planting orchards, and preparing meadows for grazing.

But with independence in 1783, Moale’s heirs soon gained the freedom to sell their landholdings. The new Maryland legislature revoked English legal practices such as the “dead hand,” and development of the peninsula followed as the area made the most of the booming town across the harbor.

When Baltimore finally became a city in 1797, it was concentrated north and west of the harbor. It wasn’t until 1817, when the city expanded its borders, that our peninsula was absorbed into Baltimore, becoming the city’s southern boundary for the next century until the Patapsco’s Middle Branch and a portion of Anne Arundel County were annexed in 1918. – Chris Everett and Steve Cole