(This story originally appeared in the December 2025 print edition of the South Baltimore Peninsula Post.)

By Steve Cole

On November 10, a drilling crew sent by Baltimore City began probing deep beneath the sidewalk on the 600 block of E. Clement Street near Key Highway to find out whether 19th-century caverns discovered there almost 75 years ago were once again threatening homes on the block.

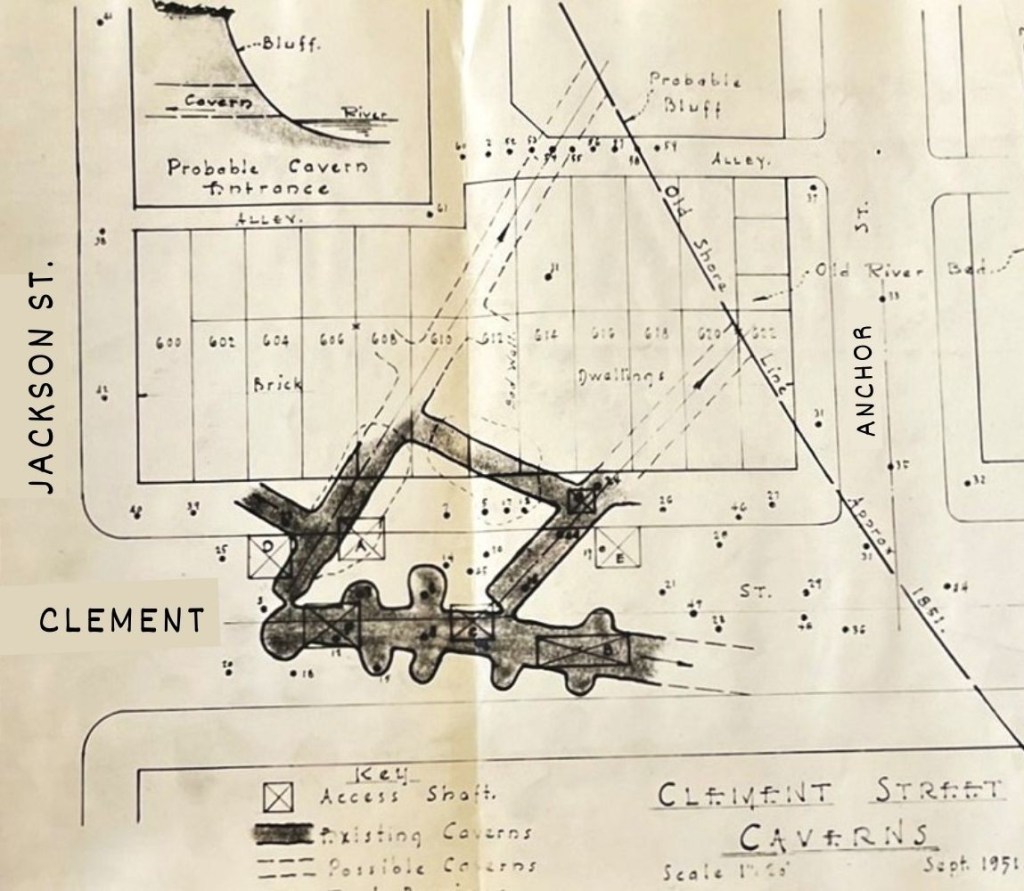

In 1951, six adjacent rowhouses in the middle of the north side of this block were torn down after City officials unearthed a series of man-made tunnels below the street that eroded basements and cracked walls, rendering the homes unsafe to live in. The six lots, eventually taken over by the City, have never been redeveloped and are now covered with landscaping and a parking lot.

Contractors working last month for the Department of Transportation (DOT) drilled five soil borings to a depth of up to 40 feet through the sidewalk in front of where the rowhouses once stood. That work extended an investigation into the subsurface stability of the area conducted a year ago by the Department of Public Works. According to DPW, that survey used ground-penetrating radar to detect some subsurface voids, but the technology could only “see” to a depth of six feet.

The City’s investigation was sparked by a 311 call from the owner of one of the E. Clement Street rowhouses standing next to the parking lot. Nancy Waldhaus made the call in April 2024 after a crepe myrtle tree a few yards from her house sank about a foot into the ground following a hard rain. She then noticed damage to her house.

“In my basement bathroom, the floor and the ceiling started separating and the floor started slanting a little,” she recalls. “I could put my finger between the baseboard of the wall and the floor, which I couldn’t do before.”

After small cracks appeared in the front wall and a gap developed between her front steps and the house, Waldhaus hired a structural engineer to assess the stability of the house and recommend repairs.

Other events on the block contributed to Waldhaus’ concern that there might be a “resurgence of a ‘sink hole’ on the city lot next to my home.” She noted that several times in recent years, holes have appeared in the street that City crews have patched. A DOT spokesperson confirmed in an email to the Peninsula Post that the department has made roadway repairs on the block at least four times in the last eight years.

While sinkholes opening up in city streets and walls cracking in century-old rowhouses are not uncommon in Baltimore, there was nothing common about what lay below the 600 block of E. Clement Street.

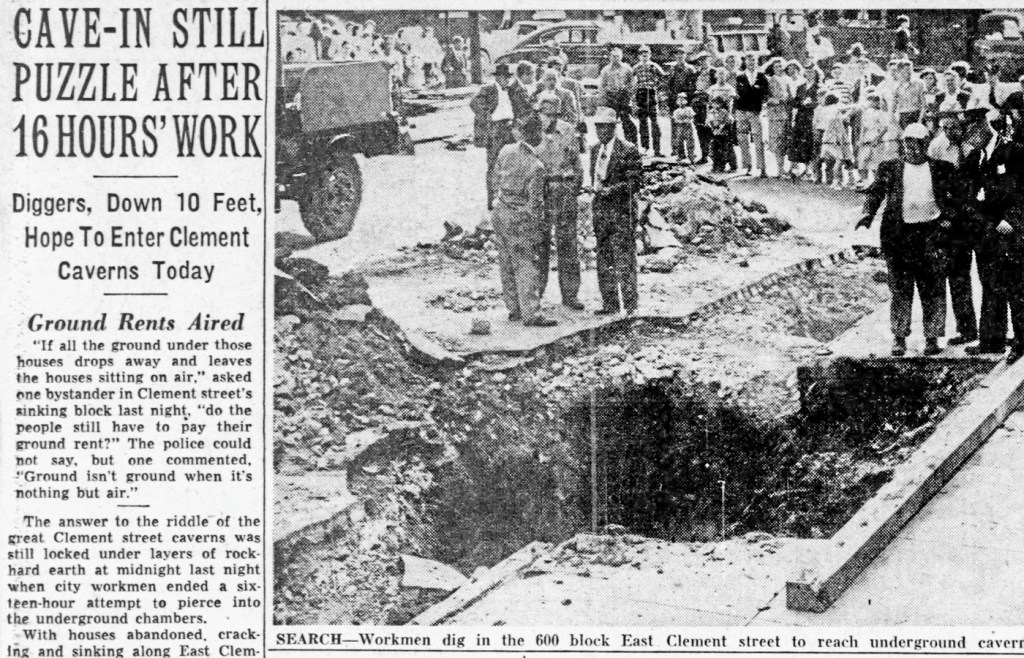

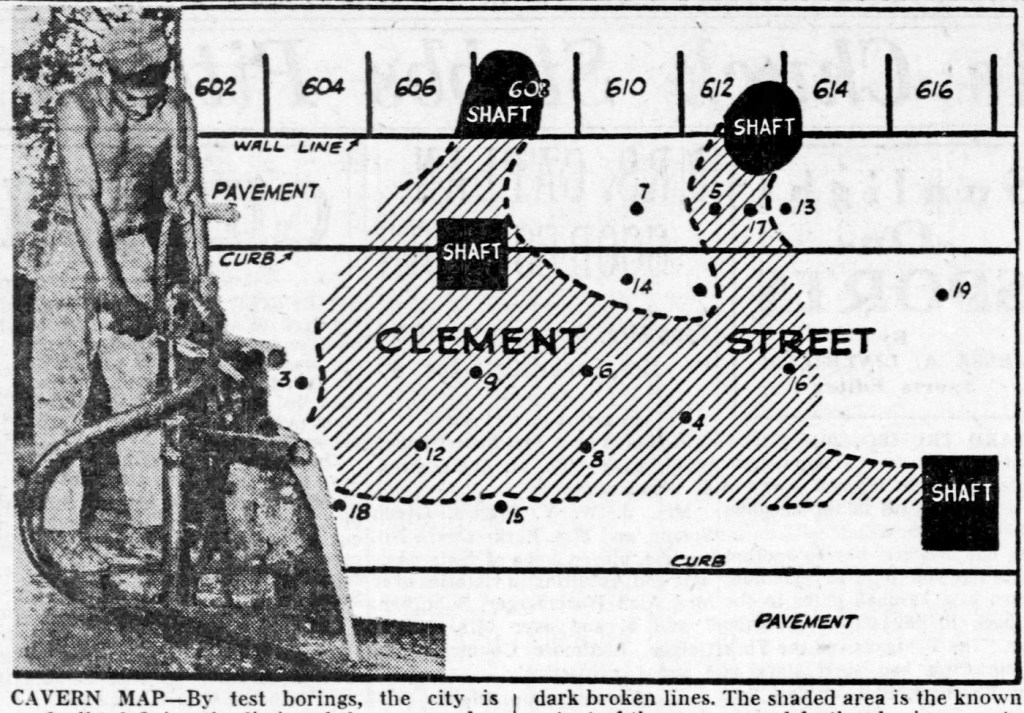

After parts of the cellars of a few of the houses on the north side of the street fell away into blackness on Sunday, June 10, 1951, the City closed the block and immediately began excavating into the street to get to the bottom of the near-calamity. (None of the residents were injured, but all immediately evacuated.) What they found after weeks of effort was a series of man-made caves about 30 feet below the surface, each 6 to 8 feet around.

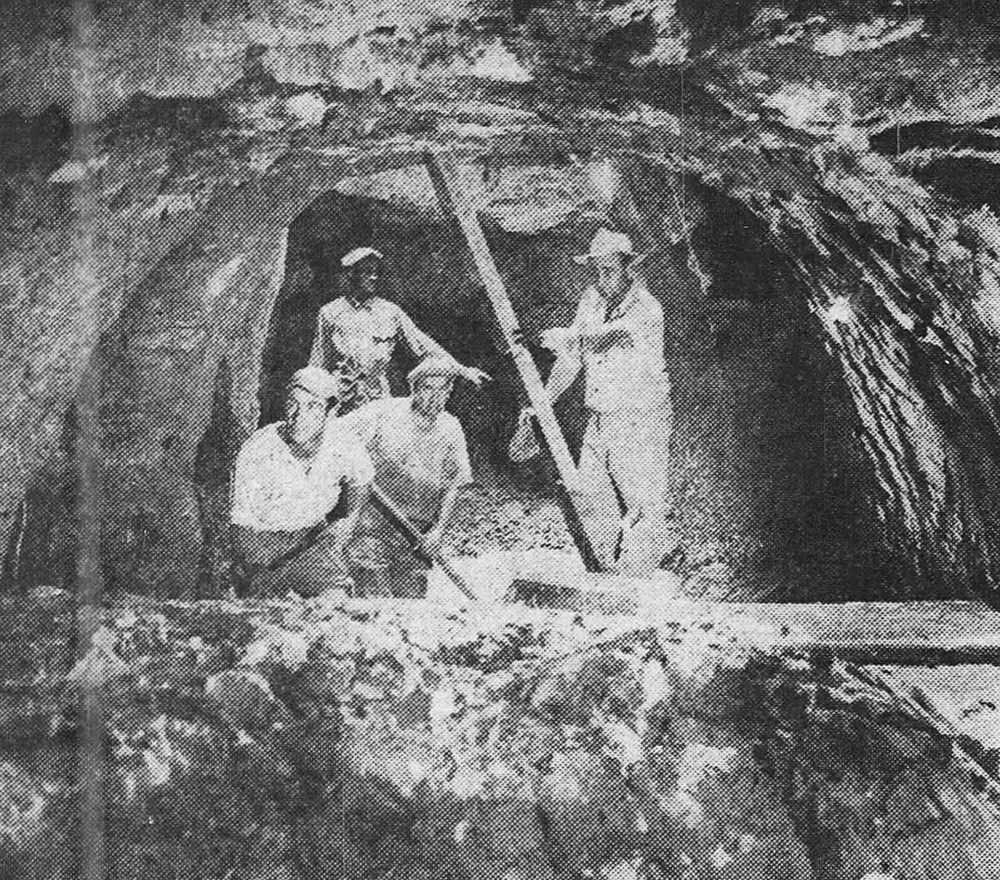

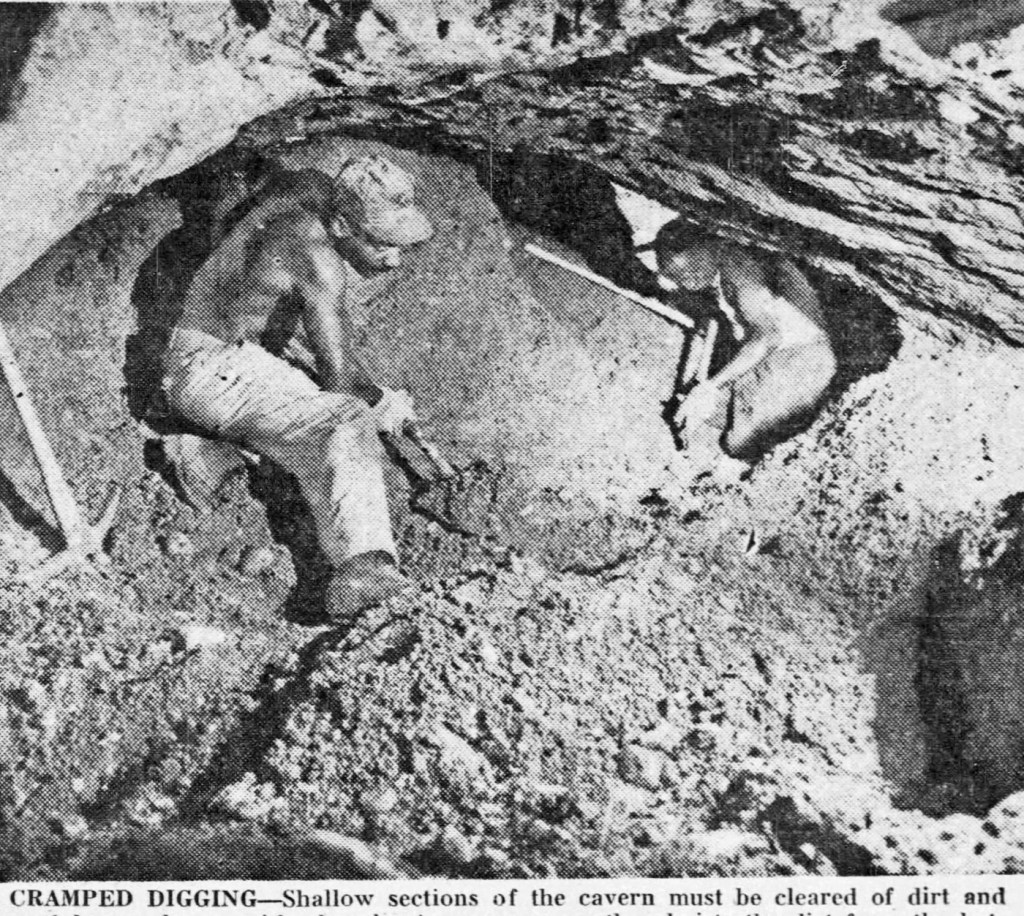

According to the official “Clement Street Caverns” report written by deputy highways engineer William L. Chilcote in 1951, who led the excavations, the roofs and sides of the caverns were arched “and the original ‘pick marks’ are still clearly visible in the hard white sand,” which was mined for glassmaking. “Apparently these caverns were dug in from a ‘bluff’ or bank that extended along the old shoreline,” he wrote. Chilcote estimated that these “sand caverns” dated back to at least the 1870s.

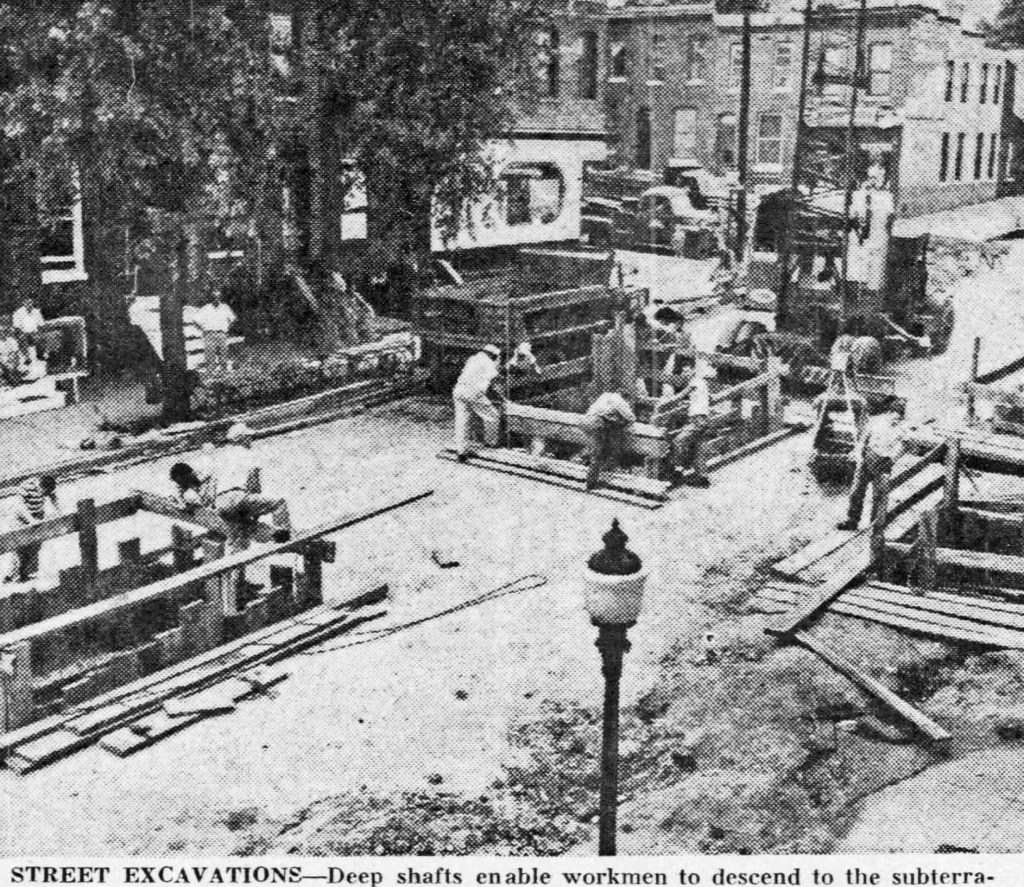

In June and July 1951, workers dug several vertical shafts through the street to explore the long-forgotten caverns. Chilcote and others descended into them and documented what they saw. Photographs of their subterranean discoveries appeared in local newspapers for weeks. Sixty-one soil borings were drilled in the area to further probe the extent of the caverns.

In Chilcote’s analysis, the caverns caved in when they did due to a slow process of erosion from within. “After the entrance of these caverns was closed and ground water trapped within them, this water, over a long period of years, attacked the overhead structures and through capillary action softened the overlying materials and weakened them to a point where they became unstable and started to cave in.”

An editorial in The Baltimore Sun commented on the jarring impact of the discovery on residents of the block. “The neighborhood has had one of the most unpleasant of all possible experiences – the discovery that at least part of it has been perched over a void. …The shock of learning suddenly of a Sunday afternoon that one’s residence rests on the least substantial of all possible foundations is an extremely nasty one.”

After completing its explorations in August 1951, the City filled in the shafts it had dug and the caverns themselves with 1,500 tons of sand and gravel. That November, the six condemned houses (606 to 616 E. Clement Street) were torn down. The people who lost their homes moved into other houses in the city purchased with private funds raised by the “Clement Street Assistance Committee” organized by Mayor Thomas D’Alesandro. By 1953, the City had acquired the empty lots, which were eventually made into a playground.

Seventy-three years later, when the Department of Public Works surveyed the area in June 2024 after Waldhaus’ 311 call, they detected underground voids beneath the sidewalks, parking lot, and a portion of the street. They also confirmed that no DPW utilities were impacted by or involved in creating the voids. Later that year, the investigation was transferred to the Department of Transportation for further action.

The goal of the recent drilling project, according to DOT documents reviewed by the Peninsula Post, is limited to investigating “the condition of the soils near the backfilled vaults” beneath the sidewalk and street. A report on the findings and proposed next steps will be issued to DOT by the contractors (STV Inc. and EBA Engineering, Inc.). According to a DOT representative, no timeline has been set for the release of the findings.

And so Waldhaus continues to wait – and worry – about the future of her home.

“All I want is to do the repairs on my house. I want to know if I have stable ground under the house,” she said. “I’ve costed out doing borings myself and putting a support in, but if there is nothing to put a support into, that makes no sense.”

In one of her many pleas to City officials about her dilemma, she wrote: “I can’t sell, I can’t repair, I can’t sleep … until the City closes out their assessment and gives me some direction.”

Additional Newspaper Coverage from 1951

June 11, 1951, Baltimore Sun

June 12, 1951, Baltimore Sun

June 20, 1951, Baltimore Sun

July 7, 1951, Evening Sun

July 7, 1951, Evening Sun

November 10, 1951, Evening Sun