(This article originally appeared in the October 2024 issue of the South Baltimore Peninsula Post.)

By Robert Hardy

Rising high above the piers and rail lines along the north shore of Locust Point, the Silo Point condominium complex stands as a 24-story-tall witness to the peninsula’s past once dominated by railroads and shipping. The structure repurposes a massive concrete grain elevator opened by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad 100 years ago this fall, which was erected to replace wooden grain elevators from the 1870s that were destroyed by fire.

That repurposing and a look back at the dominant role the B&O once played in Locust Point are documented in a new book celebrating the centennial of the grain elevator and tracing its redevelopment. Silo Point: The New B&O Grain Elevator at Locust Point by Cathie “CZ” Zimmerman (BookBaby, 2023) is a photo-heavy love letter to local history and to the iconic residential building that opened in 2009.

As Zimmerman recounts in clear, spare text and illustrates with an extensive collection of historical and contemporary photographs, the railroad influenced the history, appearance, and day-to-day life of Locust Point in profound ways. Starting in 1845, the B&O purchased land on the north shore of what was then called Whetstone Point for developing a rail and marine terminal with facilities to handle coal, grain, and merchandise. The eight acres originally acquired by B&O were located along the 2,600 feet of waterfront now occupied by Domino Sugar and Under Armour.

The first piers opened in 1848 and initiated a period of growth and prosperity for the railroad and for the community. “Over the next decade,” Zimmerman notes, “an extensive network of piers, wharves, warehouses, freight yards, and grain elevators were constructed.” Growth accelerated after the Civil War, when Locust Point was established as an immigration center and facilities were built to accommodate the influx of shipping and European immigrants. In the 1870s, the B&O filled in acres of land across the peninsula, laid miles of track, and expanded facilities further, including building its first grain elevators.

A grain elevator is a specialized warehouse and machinery complex, elevated above the adjacent piers so that grain flows by gravity into a ship’s hold for export. Bulk products like grain came by rail to warehouses and transfer facilities on the waterfront, each specialized to handle large volumes of specific products, including tobacco, grain, and coal for export and imported sugar and coffee.

The B&O built three grain elevators between 1872 and 1881. Elevator A was the first one, located on what was then Pier 5, just south of the steamship piers and immigration terminal. The wood-framed, slate-roofed structure could store 500,000 bushels of grain. In 1873, the facility exported more than 7 million bushels. Elevator B, also wood framed, opened in 1874 and could hold 1.5 million bushels. It stood on Pier 4, supported by more than 11,000 pilings, just south of Elevator A.

Within the decade, still more capacity was needed, and Elevator C on Pier 3 opened in 1881. Iron framed and covered with slate and brick, standing 174 feet tall, this largest of the three elevators had a capacity of 1.8 million bushels.

Early in 1921, the B&O began renovating and upgrading the Locust Point facilities, implementing improved methods and building new facilities for grain cleaning, dust control and removal, and, significantly, fire prevention and protection. A fire caused by a lightning strike destroyed Elevator A in 1891. As Zimmerman notes, “Crammed into the small Locust Point terminal were two elevators, several covered piers, warehouses, a large rail yard, transfer bridges, and a lot of machinery, all surrounded by acres of flammable grain and merchandise. The fire risk was staggering.”

On the evening of July 2, 1922, as a rainstorm raged across Baltimore, lightning struck Elevator B. As the Baltimore Sun reported, “There followed a sweep of flames that wrought property damage equaled in Baltimore only once since the great fire of 1904.” Along with front-page photographs of the fire consuming the warehouse on Pier 5 and of firefighters battling massive flames rising from Elevator B, the Sun recounted the destruction of both elevators and their contents (1,274,000 bushels of grain), two piers and warehouses full of merchandise, and other structures that “crumbled within a furnace that stretched along the waterfront over an area of six city blocks.”

One of the most terrifying twists of the disaster came as the flames approached the hospital complex at Fort McHenry that was built in 1917. “Fire brands whipped through the air at great heights,” the Sun reported, “rained throughout Locust Point, every section being menaced as the high winds changed. A torrential downpour of rain alone saved the wards at Fort McHenry just as the roofs began to smolder.” Ambulances and a host of volunteers evacuated 400 war veterans and other patients to shelter in School No. 76 on Fort Avenue.

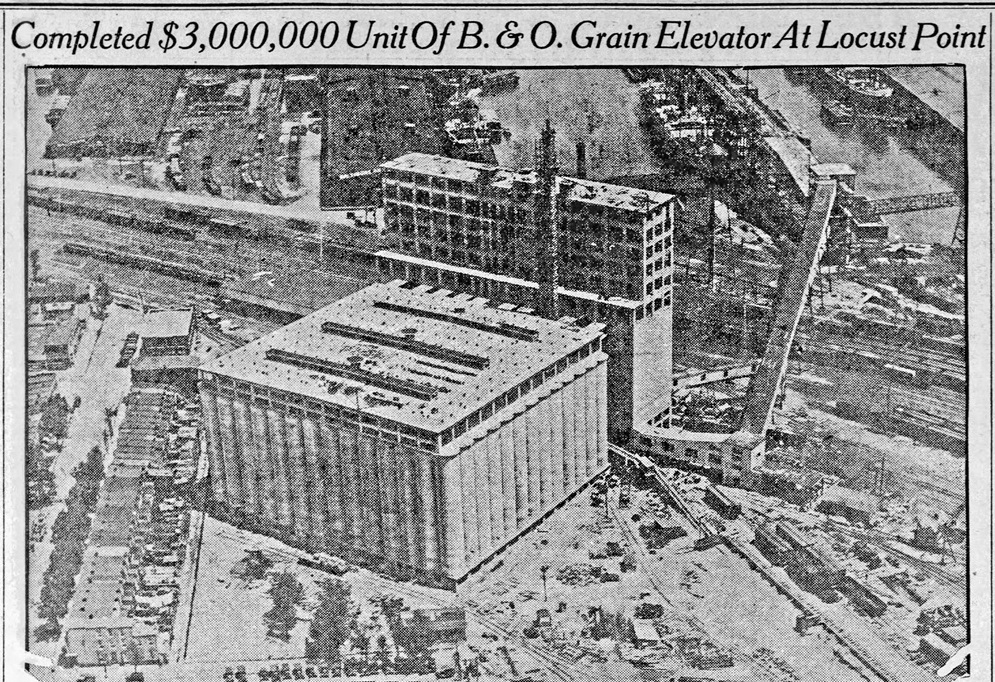

The damage and losses were extensive, and the disruption of commerce was significant. On the night of the fire, however, B&O President Daniel Willard vowed to rebuild the Locust Point facilities. And within a year, plans were completed and construction had begun on a new, modern, reinforced-concrete elevator, 206 feet tall with a 15-story “work house,” which would be “one of the most efficient and rapid grain handling plants in the world,” according to Zimmerman.

On September 9, 1924, the front page of the Sun featured a photograph of the new elevator complex, announcing the impending commercial opening of the facility within the week. The new elevator’s capacity was 3 million bushels, with the ability to handle an additional 800,000 bushels in the adjoining work house.

Zimmerman’s Silo Point walks the reader through the century between the opening of the “new” Locust Point grain elevator and its conversion to residential condos with a wealth of detail and an array of photographs. The author covers the productive years of the state-of-the-art complex and the decline of the railroads after World War II, the dissolution of the B&O, and sale of the elevator to a private firm in the 1960s.

The grain business peaked in Baltimore in the 1950s, then steadily declined as grain elevators began to disappear along the East Coast. A grain elevator in Port Covington owned by the Western Maryland Railway closed in the late 1970s. A public elevator owned by the Northern Pacific/Pennsylvania Railroad operated until 1994. B&O sold the Locust Point elevator in 1967, but it continued operations until 2001 when a storm caused the collapse of Pier 7 and the conveyor system. “Passing without much notice,” Zimmerman wrote, “this event signaled the end of the city’s earliest trade.”

It was only a few months later that developer Patrick Turner began pursuing purchase of the obsolete facility, the sale of which ultimately resulted in the development of the 24-story, 228-unit Silo Point condominium complex. Zimmerman, a current Silo Point resident, fills her book with descriptions and photos of every phase of development and construction of this South Baltimore jewel of adaptive reuse.

One thought on “From Grain Elevator to Luxury Condos in the Sky”